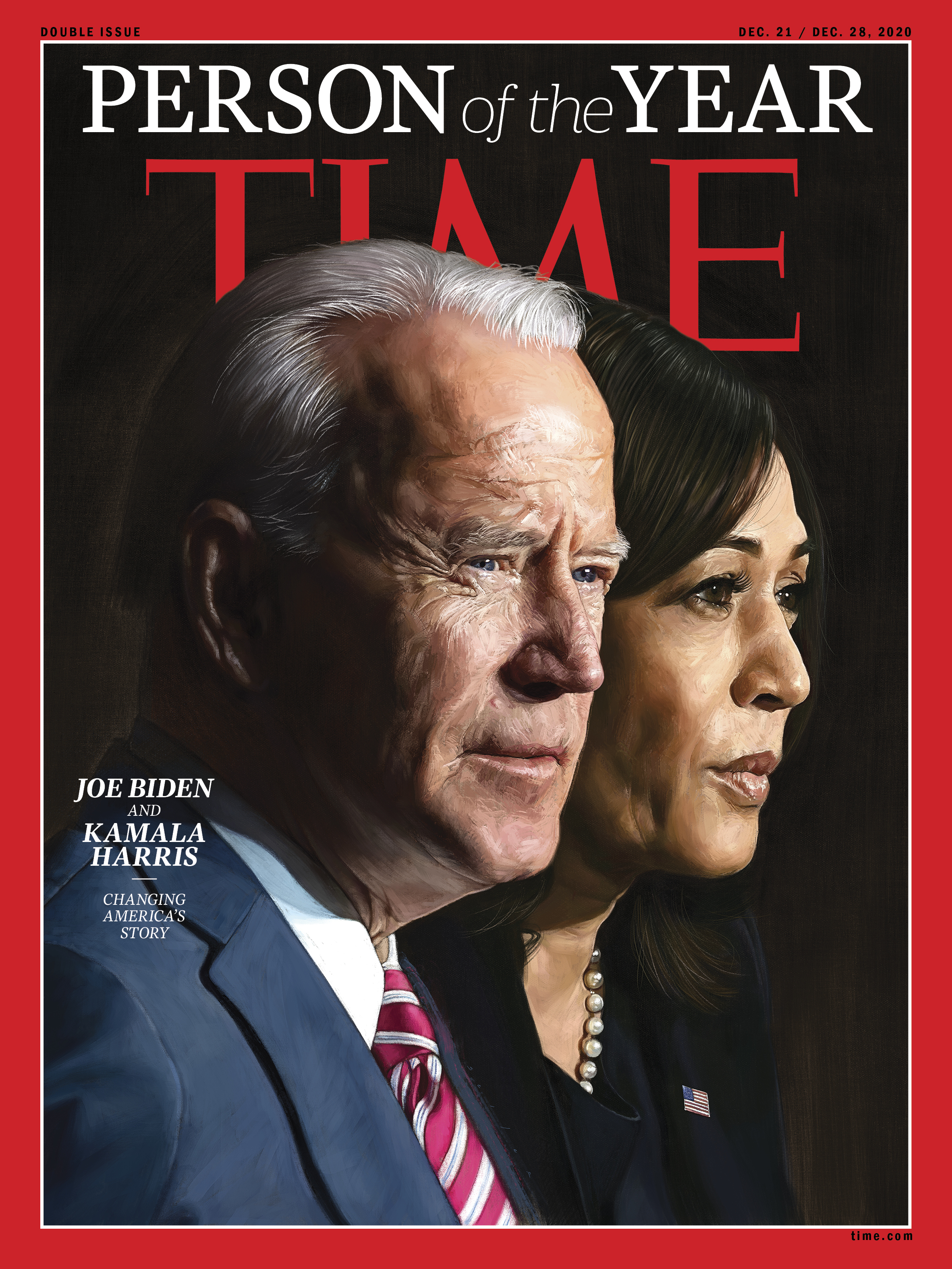

Biden and Harris named Time’s Person of the Year

As Biden sees it, trusting his instincts and tuning out the naysayers is a big reason why he’s going to be the next Commander in Chief. They said he was too old, too unsteady, too boring. That his pledge to restore the “soul of the nation” felt like antiquated hokum at a moment when Hurricane Trump was tearing through America, ripping through institutions, chewing up norms and spitting them out.

“I got widely criticized,” Biden recalls, for “saying that we had to not greet Trump with a clenched fist but with more of an open hand. That we weren’t going to respond to hate with hate.” To him, it wasn’t about fighting Trump with righteous vengeance, or probing any deeper rot that might have contributed to his ascent. Biden believed most voters simply wanted reconciliation after four years of combat, that they craved decency, dignity, experience and competence. “What I got most criticized for was, I said we had to unite America,” he says. “I never came off that message.”

Biden had the vision, set the tone and topped the ticket. But he also recognized what he could not offer on his own, what a 78-year-old white man could never provide: generational change, a fresh perspective, and an embodiment of America’s diversity. For that, he needed Kamala Harris: California Senator, former district attorney and state attorney general, a biracial child of immigrants whose charisma and tough questioning of Trump Administration officials electrified millions of Democrats.

The Vice President has never before been a woman, or Black, or Asian American. “I will be the first, but I will not be the last,” Harris says in a separate interview. “That’s about legacy, that’s about creating a pathway, that’s about leaving the door more open than it was when you walked in.”

The Democratic ticket was an unlikely partnership: forged in conflict and fused over Zoom, divided by generation, race and gender. They come from different coasts, different ideologies, different Americas. But they also have much in common, says Biden: working-class backgrounds, blended families, shared values. “We could have been raised by the same mother,” he says. In an age of tribalism, the union aims to demonstrate that differences don’t have to be divides.

No one knows the nature of this type of partnership better than Biden, who lived for eight years in the house Harris is about to move into. He has made the same commitment to her that he extracted from Barack Obama: that the VP will be the last person in the room after meetings, consulted on all big decisions. The two communicate every day, by telephone or text message, and Harris has offered welcome advice on Cabinet selections. “The way that he refers to himself and her when he speaks, he’s already making his biggest decisions with her at [his] side,” says Maya Harris, Kamala’s sister and closest confidant. Picking her as running mate “obviously has historic significance,” she says, “but clearly it’s been a choice that’s not about symbolism. It’s substantive.”

Together, they offered restoration and renewal in a single ticket. And America bought what they were selling: after the highest turnout in a century, they racked up 81 million votes and counting, the most in presidential history, topping Trump by some 7 million votes and flipping five battleground states.

Biden and Harris onstage in Wilmington, Del., at the end of the Democratic National Convention, which was held virtually because of the pandemic.Olivier Douliery—AFP/Getty Images

Defeating the Minotaur was one thing; finding the way out of the labyrinth is another. A dark winter has descended, and there will be no rest for the victors. Trump is waging information warfare against his own people, the first President in history to openly subvert the peaceful transfer of power. The country has reached a grim new milestone: more than 3,000 COVID-19 deaths in one day. Millions of children are falling behind in their education; millions of parents are out of work. There is not only a COVID-19 crisis and an economic crisis to solve, but also “a long overdue reckoning on racial injustice and a climate crisis,” Harris says. “We have to be able to multitask.”

Given the scale and array of America’s problems, the question may not be whether this team can solve them but whether anyone could. U.S. politics has become a hellscape of intractable polarization, plagued by disinformation and mass delusion. Polling shows three-quarters of Trump voters wrongly believe the election was tainted by fraud. After four years of a White House that acted as a celebrity-driven rage machine, it seems naive to think of the presidency as an engine of progress.

So while Biden will be the 46th man to serve as President, he may be the first since Lincoln to inherit a Republic that is questioning the viability of its union. “This moment was one of those do-or-die moments,” Biden says. “Had Trump won, I think we would have changed the nature of who we are as a country for a long time.” Yet Trump, many experts argue, is not the aberration Biden describes but rather a symptom of America’s chronic conditions: a legacy of racism and widening inequality that undermines both its ideals and its functioning.

Biden and Harris share a faith that empathetic governance can restore the solidarity we’ve lost. Biden told TIME he has lately been reading about Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days, when FDR worked to pull the nation out of the Great Depression, a feat that helped restore confidence in democracy. “We’re the only country in the world that has come out of every crisis stronger than we went into the crisis,” he insists. “I predict we will come out of this crisis stronger than when we went in.” Their challenge is, above all, not about any one policy, proposal or piece of legislation. It is convincing America that a future exists, for all of us, together. It is nothing less than reconciling America with itself.

They are partners now, but they were rivals once. When the Democratic primary candidates met for their first debate in June 2019, Biden was the front runner, though he didn’t look much like one. His organization was rickety, his speeches baggy, his message seemingly out of step with the party’s mood. Harris looked equally lost, stagnant in the polls and shuffling campaign messages. After launching her campaign with fanfare—20,000 people turned out to her kickoff rally in Oakland, Calif.—she struggled to find her footing in a crowded field.

On a hot night in Miami, the Democrats’ past and future collided. Advisers had warned Biden that rivals would target his sepia-toned musings about compromises struck in Senate cloakrooms. But he wasn’t ready for Harris’ attack. “As the only Black person on this stage, I would like to speak on the issue of race,” she said, turning to address Biden. She told him it was “hurtful” to hear him praise segregationist Senators who had been his colleagues. “Not only that, but you also worked with them to oppose busing,” she continued.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me.” To Harris’ supporters and many more African Americans, the moment was a battle cry. Biden backers saw an ambush: within hours, her campaign had designed T-shirts with Harris’ childhood picture above those words.

Biden campaigns in New Hampshire on Feb. 9; his fifth-place finish in the primary was a low point, 18 days before his win in South CarolinaTony Luong for TIME

In fact, the issue was more complex than it seemed. In the 1970s, Biden opposed federally mandated busing, not voluntary programs like the one Harris had participated in in Berkeley. Nor did Harris believe a federal mandate was necessary; her own stance was nearly identical to Biden’s.

But to many Americans, it was powerful to see the only Black candidate onstage discuss sensitive policy through the prism of her lived experience. There was neither mystery nor malice to the confrontation. Harris was searching for momentum, and Biden was the primary’s piñata; to many, it seemed inevitable that he would fade, and whoever took him down might inherit the favor of the Democratic establishment.

But Biden was taken aback. Harris had been close with his son Beau while they both served as attorneys general of their states. Despite criticism of his involvement with regressive criminal-justice policy in the 1990s, Biden’s longtime advocacy for civil rights was a point of personal pride and had helped earn him the loyalty of many Black voters.

While Biden did not hold a grudge, advisers say, his family, particularly his wife Jill Biden, was upset. Today, she concedes the exchange was a “surprise” because of Harris’ friendship with Beau, who died of brain cancer in 2015, but noted others on the debate stage criticized Biden as well. “This is a marriage, and I feel very protective of my husband and my children, as is any mother,” she tells TIME. “You move beyond it—that’s politics.”

Whatever boost Harris got in the primary was short-lived. She ran low on cash, sank in the polls and dropped out of the race in December. Biden seemed not far behind, limping to a fourth-place finish in Iowa and slipping to fifth in New Hampshire. That was the “lowest point,” Jill Biden recalls. “I had a feeling we weren’t going to win, but I didn’t think we would come in fifth. Nor did Joe.”

Harris stops for lunch in Waterloo, Iowa, in September 2019; she abandoned her presidential bid less than three months laterSeptember Dawn Bottoms for TIME

Biden had always believed his support among Black voters would buoy his campaign in the Feb. 29 South Carolina primary. After a key endorsement from House majority whip Jim Clyburn, he won by nearly 30 points, establishing himself as the most credible alternative to Senator Bernie Sanders, who had been threatening to run away with the race. Fearful that a Sanders nomination would mean a second term for Trump, Biden’s moderate rivals Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar dropped out and endorsed him. Soon after, Biden cleaned up on Super Tuesday, winning 10 of 14 states and effectively clinching the contest. Harris endorsed Biden the next weekend, the 55th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, just before walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., with Representative John Lewis.

Biden felt vindicated. Progressives had insisted the party was in a revolutionary mood; instead, voters chose Biden’s pragmatism. Doubters predicted Biden’s record on race would haunt him; instead, he had Black voters to thank for reviving his campaign. Critics had lampooned “unity” as boring pabulum; instead, it seemed to resonate. “I was able to, against advice from a lot of people, do the things that I was told were gonna hurt me politically,” Biden says. “But I would argue that it turned out that that’s what the American people were looking for: they’re looking for some honesty, decency, respect, unity.”

Just as he found his footing, the ground shifted beneath his feet. By March 10, it was clear that the corona-virus would make it impossible to run a traditional campaign. “It was the culmination of all of the work that we’ve done for a year,” says Biden’s deputy campaign manager and incoming White House communications director Kate Bedingfield. “And we were having to think about, How are we going to reinvent campaigning in the general election?”

Biden canceled a planned rally in Ohio and returned to Philadelphia to speak to the whole staff in person for the last time. The campaign headquarters emptied out; the team retreated to their couches, where they marshaled volunteers online and tried to build camaraderie over Signal and Zoom. Biden himself retreated down the winding driveway to his 7,000-sq.-ft. home in Greenville, Del., past poplars, beech and oak trees, to his book-filled study overlooking a lake, where he would spend much of the next eight months.

Campaigns are fueled by excitement; Biden didn’t seem to have it. The situation had its advantages: being homebound disciplined a gaffe-prone candidate, and his themes of empathy and compassion resonated amid the ravages of COVID-19. But running for President online also neutralized Biden’s ability to connect with ordinary people through hugs and handshakes. The candidate’s lack of visibility meant picking a running mate would be one of his few big turns in the spotlight, and a more momentous decision than usual.

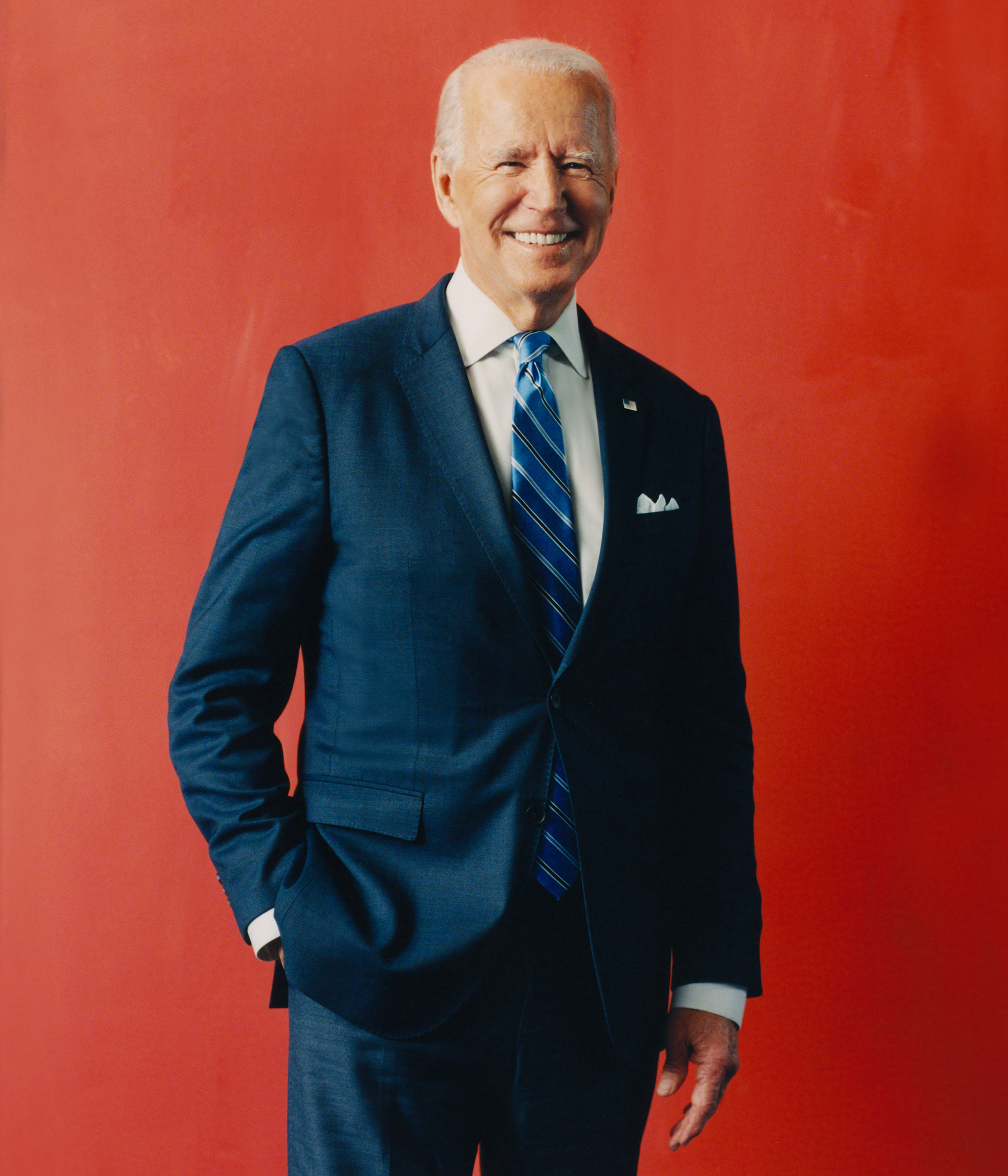

President-elect Joe Biden photographed in Wilmington, Del., on Dec. 7Camila Falquez for TIME

Biden was looking for his own Biden: someone reliable, simpatico and loyal, as he was to Obama. But he wanted more than compatibility. The septuagenarian nominee needed a youthful governing partner who was prepared to step in as Commander in Chief if needed, and a battle-tested running mate who would not create distractions and could keep the race focused on Trump. As an old white man leading a party reliant on voters of color, young people and women, Biden also needed to balance the ticket. In March, he had promised to pick a female Vice President; over the summer, the racial-justice protests that erupted after George Floyd’s killing increased pressure to choose a Black woman.

Biden’s selection committee, augmented by a team of vetting lawyers, initially interviewed nearly two dozen women, before whittling the list down to 11 people for Biden to interview. After Floyd’s death put racial justice front and center, Harris stood out in her conversations with the committee, discussing criminal-justice legislation she was leading in the Senate and her work on similar issues as attorney general. “She also brought a lived experience as a Black woman,” says Representative Lisa Blunt Rochester, who served as co-chair of the vetting committee. “She could talk from the perspective of her professional life as well as her personal life, and what we could and should do in the wake of his tragic murder.”

At 55, Harris was a generation Biden’s junior. She had experience in federal and state office, and had weathered the scrutiny that comes with running for President, even if her campaign didn’t succeed. She was a versatile politician, moving deftly from dissecting witnesses in hearings to dancing in drum lines. No major factions in the party opposed her, and most Democrats thrilled to the idea of putting the first woman of color on a major presidential ticket. But Biden, the connection candidate, didn’t just see a symbol or an appeal to a particular demographic; he perceived an ability, rooted in her upbringing, to see a better future for Americans like herself. “Her superpower is her multiple identities,” says Glynda Carr, CEO of Higher Heights, a political action committee that helps Black women run for office.

Some Biden allies remained wary of Harris. His family was the hardest sell. But Biden insisted he harbored no hard feelings from the debate skirmish. “He made it very clear that he was a big boy and wasn’t going to let that color him,” says Clyburn, who urged Biden to pick a Black woman and told him that many people, including Clyburn’s own late wife, had rooted for a Biden-Harris ticket from the start. Once Biden decided Harris was the best pick, the rest of the inner circle got behind the decision. Jill Biden was the one who called the vetting committee to inform them of the choice. “At the end of the day, it was his decision, and one that he made essentially alone,” Bedingfield says.

Vice President–elect Kamala Harris photographed in Wilmington, Del., on Dec. 7Camila Falquez for TIME

Harris was in her apartment in Washington’s West End neighborhood when her team learned that Biden wanted to reach her. She started getting ready to take the call. Then, an update: Biden wanted to talk over Zoom. A brief panic ensued as she scrambled to get herself video-ready. It “wasn’t actually one of my Zoom days,” she says. “That required a whole preparation process to be Zoom-ready for the Vice President.”

Biden cut to the chase. “Immediately he said, ‘So, you want to do this?’” Harris recalls, paraphrasing their conversation. “That’s who Joe is. There’s no pomp and circumstance with him. He’s a straight shooter.” Her husband Doug Emhoff and Jill Biden soon joined them on the call; within an hour, her apartment filled with campaign staffers carrying briefing binders. The next day, she was in Wilmington, where Jill greeted them with a plate of homemade cookies.

To join the Biden campaign was to join the Biden family, and Harris and Emhoff spent about a week visiting with the Bidens and getting to know their kids, while Biden talked over the phone with Harris’ mother-in-law and her adult step-children, Cole and Ella. Harris’ relationship with Emhoff’s kids, who call her Momala, reminded Biden of his own wife’s relationship with his sons Beau and Hunter: a “blended family,” he calls it, where there’s “no distinction in their house.”

Picking a former rival—one whose dynamism might exceed his own—was a move that Trump never would have made. It “revealed a lot about Joe Biden,” says former Representative Steve Israel. “And she had the pronounced effect of mobilizing Democrats across the country.”

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. has wanted to be President ever since he was a little boy with a mouth full of pebbles, reciting poetry to try to cure himself of his stutter. When his future mother-in-law asked what he planned to make of himself, Biden said “President,” adding, “of the United States.” Before she died in a car accident in 1972, his first wife Neilia told friends her husband would run the country one day; many years later, when Biden was in the twilight of his vice presidency, his son Beau, racked with terminal cancer and beginning to lose his speech, begged him not to abandon public life. He’s run for the Oval Office three times, worked with eight Presidents and served as Vice President for eight years in a career that stretched from the Senate to the Situation Room to countless swing-state diners and union halls. His operatic life story has veered from grief to triumph, rising star to tragic figure, statesman to survivor.

Biden’s American Dream began in the rosy aftermath of World War II, when America was flush with pride from its triumph over fascism. It was a Rockwell upbringing—football games, soda-pop shops—but it wasn’t always easy. At times money was tight; when Joe was 10, the family had to move in with his grandparents before his father found a job selling used cars. Although popular and outgoing, Biden was afflicted with a persistent stutter, which instilled in him a lifelong hatred of bullies and a belief that even the most stubborn obstacles could be overcome. “My mother’d say, ‘Joey, remember, the greatest virtue of all is courage,’” Biden recalls. “Without it you couldn’t love with abandon. And all other virtues depend on it.”

While other teenagers marched against the Vietnam War, Biden glad-handed around the University of Delaware in a sport coat. He was never the best student or hardest worker, but his charm and talent carried him through law school, a brief stint as a public defender and a seat on the New Castle County council. In 1972, as Harris was being bused to third grade, Biden mounted a long-shot bid for Senate. He courted comparisons to John F. Kennedy: a young, ambitious candidate with a big Irish-Catholic family, a photogenic wife and adorable kids, and a message about bringing a new generation to power. Congress had recently lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, and Biden’s sister Valerie, then as now his closest political adviser, organized a brigade of high schoolers to knock on thousands of doors, lifting the 29-year-old to victory over a two-term incumbent.

Just weeks later, the car carrying Biden’s wife and children on a Christmas shopping excursion was broadsided by a truck. Neilia and their 13-month-old daughter Naomi were killed. Biden’s two sons were badly injured. He came close to quitting the Senate before he was sworn in. “His grief makes him human,” says Moe Vela, a former senior adviser. “And he understands that shared humanity, that shared vulnerability, allows him to connect.”

From left: Biden and Jill, his future wife, met in 1975; Harris with her younger sister Maya and mother Shyamala Gopalan in 1968Courtesy Jill Biden; Courtesy Kamala Harris

As a Senator, Biden was rarely behind the times, but rarely ahead of them either. As Judiciary Committee chair, he oversaw the hearings into Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, enraging many for not including public testimony by additional witnesses who could testify to Thomas’ pattern of behavior and for allowing the all-white, all-male committee to bully Hill. He championed the 1994 crime bill, which included both tough new sentencing laws and the Violence Against Women Act. He voted for the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman, then, nearly two decades later, upstaged Obama by embracing same-sex marriage before the President did. He was a politician who followed public opinion but did not guide it, an institutionalist who believed in the moderating influence of the Senate almost as much as he believed in his own policy preferences.

He carried that disposition into the vice presidency. Once, when Vela was flying to Chile with Biden on Air Force Two, the aide complained in personal terms about a Republican Senator who was blocking an Obama proposal. Biden grabbed Vela’s left forearm with his right hand, as Vela recalls it, and said, “Moe, you’re wrong. That’s my friend.

We might not agree every time on how to make America better, but we both agree that we want to make America better.” Biden advised younger politicians to criticize their rivals’ policies without impugning them personally. “Once you start attacking people’s character and their motivations, you prevent them from ever being able to get over the policy disagreement you had, and you lose them as someone you can potentially work with,” explains Delaware Senator Chris Coons, a Biden protégé.

Biden went out of his way to help Republicans where he could, once flying to Moscow and back in a single day to join a GOP colleague for a presentation on nuclear weapons. “Joe has a good heart,” says former Republican Senator John Danforth. “He’s got the temperament and the background to reach out and to work with all kinds of people to make government work again.”

Most of all, Biden became famous for his empathy. The stories are legion: how he hugged a grieving child; called a grandmother on the day her grandson was sworn into the Senate; reached out after a car accident, a cancer diagnosis, a death in the family. One former adviser recalled how Biden held up his entourage on the way out of the Executive Office Building to offer heartfelt thanks to a janitor for mopping a spill; another recalls he and Jill always sent food to the drivers waiting for them outside.

During a photo shoot for this story, Biden asked the photographer, Camila Falquez, to FaceTime her parents. “Hola, Mami!” Falquez said as they came on the screen. “Hey, Dad, how are you?” Biden interjected, briefly pulling down his mask so the pair could see his face. “You guys have a wonderful daughter.”

Although Obama picked him in part because he believed Biden had put his presidential ambitions behind him, Biden toyed with running in 2016. He ultimately decided he wasn’t up to it in the wake of Beau’s death. But in 2017, when white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, Va., he decided he had to get back in the game. “He could not have lived with himself if he hadn’t run after Charlottesville,” says Biden’s longtime adviser Ted Kaufman, who is heading the presidential transition. “If he didn’t run and Trump won, he would have spent the rest of his life feeling he could have beaten Trump.”

As Biden was muscling his way through public-speaking requirements at Archmere Academy near Wilmington, in 1958, 19-year-old Shyamala Gopalan arrived in Berkeley to pursue a doctorate in nutrition and endocrinology. She soon realized that she had swapped one caste system for another. While her Tamil Brahman heritage signified her elite status in India, the U.S. was segmented along racial lines.

-Gopalan joined a Black study group whose discussions on race helped inform the intellectual underpinnings of the Black Power movement. Malcolm X, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro were considered heroes, one of the group’s leaders, Aubrey LaBrie, told TIME last year. It was there that Gopalan met a Jamaican economics student named Donald Harris. They had two daughters, Kamala and Maya, before divorcing when Kamala was 7.

If Biden grew up in an age of American ascendance, Harris came of age in a nation confronting its legacy of injustice. Her parents took her to civil rights marches in a stroller. After their divorce, Kamala and Maya attended an after-school program decorated with images of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. Harris has recalled learning about George Washington Carver before she learned about George Washington.

In 1970, when she started first grade in Berkeley, Kamala was in one of the first groups of students to be bused to a mostly white school across town in an early local experiment in integration. “Mommy had great expectations for us, but she had even greater expectations of us,” Maya Harris says. “And that sense of responsibility and duty that our mother instilled in us, to leave this world more fair and more just for more people than when we entered it, that sense of responsibility and duty has guided her throughout her life.”

Harris campaigns in McAllen, Texas, on Oct. 30, part of a late play to win the Lone Star State that fell shortSergio Flores—Bloomberg/Getty Images

Although she grew up among activists and organizers, Kamala Harris wanted to make change by working within the system, not outside of it. At nearly every station in her career, she broke a barrier. In 2004, she was elected San Francisco DA; six years later, she was elected attorney general of California. The balance between “progressive prosecutor” and “top cop” was a delicate one. She implemented new programs for young nonviolent offenders, yet began enforcing truancy laws by threatening parents with fines if their kids missed school. Even in the 2020 campaign, Harris seemed to be juggling allegiances, down to her campaign slogan, “For the People,” intended to evoke her prosecutorial roots while blurring their controversial connotations.

Like Biden, she had a knack for sensing where the political wind was blowing and sometimes disappointed liberal activists. She sought to uphold questionable convictions, declined to support legislation to reduce low-level felonies to misdemeanors and tried to reinstate the death penalty, even though she claimed to oppose it. At the same time, she earned accolades on the left for taking on oil companies, for-profit colleges and predatory mortgage lenders, and for refusing to defend California’s ban on gay marriage.

As a newly minted attorney general in 2011, she pulled out of a national mortgage-foreclosure settlement with five big banks when she felt the approximately $2 billion allotted for California didn’t give her constituents adequate restitution. Ultimately she procured a $20 billion settlement. “The fact that she was an AG and had her fingers on every aspect of governance in California will help her in every role she takes in the federal government,” says Doug Gansler, a former Maryland attorney general who served with her during this time.

Harris arrived in the Senate in 2017, the first Indian American in its history. Already a political celebrity, she impressed colleagues as much with her infectious laugh as with her ruthless probing of witnesses. Then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions complained that her rapid-fire questions made him “nervous”; she reduced the current Attorney General, Bill Barr, to stammering when she asked if the White House had ever asked his Justice Department to investigate anyone. In September 2018, her calm but pointed grilling of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh went viral, enhancing her reputation on the left.

Harris played an integral role in that year’s bipartisan criminal-justice legislation and co-sponsored the liberal Green New Deal. Though she built a reputation as a serious policymaker, she never carved out a signature issue and seemed to elude ideological definition. She spent just two years in the Senate before launching her bid for President.

After clinching the nomination, Biden set to uniting his party. He won Sanders’ endorsement, solicited advice from Senator Elizabeth Warren and invited well-known progressives to offer policy ideas. “Biden’s ability to hold the party together can’t be overstated,” says veteran Democratic admaker Jim Margolis, who worked for Harris during the primary. “That was an impossible task for Hillary Clinton in 2016. In 2020, it was the name of the game.”

Biden’s political instincts were tested over and over, starting with the summer’s racial-justice protests. Trump was using images of urban riots to associate his rivals with chaos and lawlessness, even embracing vigilantes and far-right militias as symbols of a racist pro-police “law and order” message. Neither Biden nor Harris had been the first choice of racial-justice organizers. To some activists on the left, the idea of reconciliation smacked of weakness. “You call it unity, I call it capitulation,” says Alicia Garza, co-founder of Black Lives Matter and principal at the Black Futures Lab.

Biden sought a middle course. He knelt alongside activists, proposed substantive reforms to address structural racism and embraced the Black Lives Matter mantra. But he rejected calls to “defund the police” and denounced violence and the destruction of property. “I was cautioned by some really smart people. You know, ‘Don’t go out and talk about racial inequity,” Biden says. “‘Don’t mention it because you’re gonna lose the suburbs.’” He ignored them, believing the country had changed since President Richard Nixon’s coded appeals to the racial consciousness of the “silent majority.” “I think the American people are better and more decent than that,” Biden says.

To knock off an incumbent President for just the 10th time in American history, Biden and Harris had to revive the party’s fading strength with white voters without college degrees; energize its emerging base of diverse, urban young voters; and motivate the hordes of angry suburbanites, particularly college graduates and women, who had fled the Trump-era GOP. None of these constituencies would be enough to carry the Electoral College on its own, and leaning too far into any one of them risked alienating another.

A masked Biden speaks to supporters in Philadelphia on Election DayDrew Angerer—Getty Images

Biden was perhaps the only Democratic candidate who could claw back some of the party’s lost ground with the culturally conservative white voters who dominate the swing states of the Rust Belt. Harris, meanwhile, brought a cultural competency that attracted the next generation of Democrats, right down to her footwear. When she stepped out of a plane in Chuck Taylor sneakers, many voters saw a politician who had literally walked miles in their shoes. Harris’ candidacy was especially meaningful to the Black women who form the backbone of the Democratic Party, and whose turnout was critical in flipping key states. “The electorate is continuing to change, and that demographic change is the story of this election,” says Henry Fernandez, CEO of the African American Research Collaborative. “It’s reflected in Kamala Harris.”

On election night, Biden was at home in Wilmington; 13 members of his family had individually quarantined beforehand in order to watch the returns come in together. Campaign staff gathered in front of a huge screen at the Chase Center nearby. Advisers downplayed the chance of a quick victory. Still, some Democrats panicked early in the night, fearing Trump’s strength in Florida foreshadowed a repeat of 2016. Biden allies reassured supporters that mail ballots would ultimately erase Trump’s lead, but many were anxious. “I sure went to bed depressed,” says longtime donor John Morgan.

Most of the Biden brain trust didn’t go to bed at all. Every hour or two, they were briefed by the campaign’s analytics director, Becca Siegel, who assured them Biden was getting the numbers he needed. “The mood was not dire or panicky,” says Bedingfield. “It was more like the agony of waiting and waiting for something that you know is coming.” For the next four days, the Bidens were “like every other family in America: we were glued to the TV,” Jill Biden recalls.

When the networks finally called the race on Nov. 7, Joe and Jill were away from the television, sitting on lawn chairs in the backyard. All of a sudden loud cheers broke the silence, and their grandchildren came running, shouting, “Pop won!” Once inside, Biden’s first call was to Harris.

Harris saw the news after coming back from a run in Delaware. She rushed back outside to find Emhoff to tell him, and that’s when she got the call from the President-elect. As the streets erupted in celebration, her sister Maya came over for a lunch of bagels and lox, with a plate of bacon to share. For millions across America, it was the dawn of a new era after four years of vexation and strife; for the sisters, watching footage of revelers gathering in front of the little yellow apartment in Berkeley where they grew up, it was as if time had stopped. “We kind of had this brief moment where everything was bursting all around us, but we could just sit for a bit and take it all in before plunging into what was about to become this imminent new, big reality,” Maya says.

Even now, friends say, that reality hasn’t quite sunk in. Harris’ longtime adviser Minyon Moore says she keeps asking: “Do you know you’re the Vice President yet?” And Harris replies, “No, not really, but I’m trying.”

All new Presidents inherit messes from their predecessors, but Biden is the first to have to think about literally decontaminating the White House. Combatting the pandemic is only the start of the challenge, at home and abroad. There are alliances to rebuild, a stimulus package to pass, a government to staff. Biden’s advisers are preparing a slew of Executive Orders: restoring the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration program, rejoining the Paris Agreement, reversing the so-called Muslim ban and more. Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan aims to revitalize the virus-wracked economy—which some analysts say is unlikely to fully recover until 2023—by investing in infrastructure, education and childcare. “I think if my plan is able to be implemented,” Biden says, “it’s gonna go down as one of the most progressive Administrations in American history.”

Much of what Biden hopes to do, from Cabinet appointments to legislation, will have to pass a more divided Senate than the one he left a dozen years ago. If Republicans win at least one of Georgia’s two Senate seats in Jan. 5 runoffs, the fate of his agenda will be in the hands of Republican majority leader Mitch McConnell, who, like most GOP members of Congress, has refused even to acknowledge his victory. Biden’s relationships and peace offerings may not be worth much in this climate, says his friend William Cohen, a former GOP Senator. Republicans “will be watching not him but Donald Trump, and acting just as much out of fear of [Trump] in the future as they have in the past.” As in the campaign, the GOP is likely to amplify controversy surrounding Biden’s son Hunter, who on Dec. 9 released a statement acknowledging his tax affairs are under investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s office in Delaware.

Harris and Biden at a high school in Wilmington, Del., on Aug. 12Carolyn Kaster—AP

For now, Biden and Harris are busy building a team in a well-ordered sequence, starting with senior White House staff and progressing through clusters of appointments—first foreign policy, then economic officials, then health advisers, and so on. The Biden-Harris Administration is on track to be one of the most diverse in the nation’s history, though it doesn’t go far enough for some. Their relationship has continued to deepen. “The thing that I love that I’ve observed: it’s not stiff, it’s natural,” Jill Biden says. “They’re friends already, and the trust can only continue to grow.” Biden’s big jobs as Vice President—from selling the Recovery Act to negotiating budget deals with McConnell—tended to land in his lap, and he expects it will be similar for Harris, who has not yet announced a dedicated portfolio. To millions, the symbolism of Harris’ role is nearly as important as the substance. “What she’s projecting is America—it has risen just one more time,” Moore says.

Even if Trump still captivates a broad swath of the country, the President-elect believes the rancor will fade as Trump exits stage right. The next few months will be “letting the air out of the balloon,” says Biden. “I think you’re gonna see a lot more cooperation than anybody thinks.” Until then, he and Harris are polishing their scripts and rehearsing their lines inside the Queen. They have just six weeks to prepare. On Jan. 20, the lights will come up, and the show will go on. —With reporting by Alana Abramson, Brian Bennett, Vera Bergengruen, Madeleine Carlisle, Leslie Dickstein, Alejandro de la Garza, Simmone Shah, Lissandra Villa, Olivia B. Waxman and Julia Zorthian

This article is part of TIME’s 2020 Person of the Year issue. Read more and sign up for the Inside TIME newsletter to be among the first to see our cover every week.